Why?

The separation between art and science as two distinct fields with little overlap is not old. Until the 18th century, science and art were viewed as intertwined, if not the same, both enquiring about and researching the world’s phenomena. Leonardo da Vinci was a painter and scientist. Only the separation between the disciplines at the beginning of the 19th century has led to the current way of siloed science education, which STEAM tries to reunite.

In today’s society, artists and scientists don’t share common spaces any more; they all work in specialised containers. And it is pretty simple: if you don’t see each other, you can’t inspire each other. For people to connect, they need mutual visibility and sensory exchange.

By removing this artificial separation and creating an atmosphere of cross-pollination, we want to recreate the atmosphere of a world where art and science are interwoven, like in the time of Leonardo da Vinci.

How?

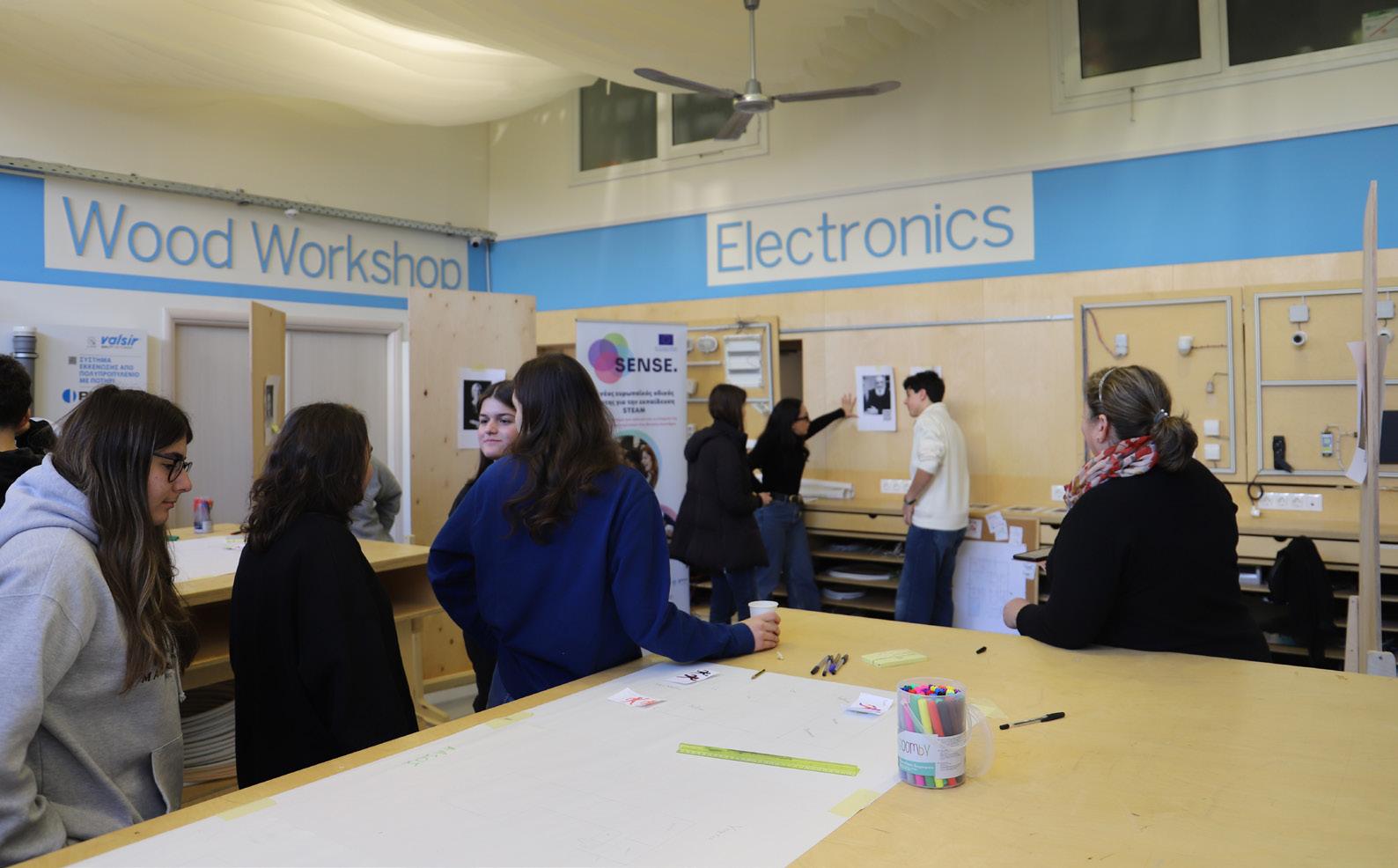

For this experiment, we need a large, flexible, and adaptable space that can accommodate a wide range of activities simultaneously. Many experimental schools, such as the Laborschule in Bielefeld or the UCL Academy in London, experiment with this kind of open-plan arrangement. Central to the success of this approach is

– having the right flexible furniture that maintains a degree of spatial separation while maintaining a tangible sensory connection between the activities. Even if it seems counterintuitive, an element of positive disruption and interference (Noise!) is crucial.

– a pedagogical approach that promotes student-centred enquiry, facilitating independent self-organised work without needing a significant proportion of tutor-centred information transfer, which is challenging in large open spaces.

Further Suggestions

At this point one might argue that the “Da Vinci Studio is just about open-plan schooling, which has never worked anyway”. Firstly, many countries, for example, New Zealand or Finland, are revisiting the model as an expression of a changed STEAM-leaning curriculum. Secondly, this experiment is NOT about open-plan schools in itself. It is about running activities of all kinds (commonly considered incompatible) in parallel and creating a buzzing atmosphere of exploration and inspiration.

Here are a few possible scenarios:

1) “Do I know you?”: Unfamiliar neighbours

This variant is well-suited as a warm-up exercise, for example, when (ideally over a few sessions) an art activity takes place in a chemical laboratory that needs to be adapted for art-making (see also the “Hack the Space” experiment). In parallel, the chemical experiments are conducted in the art space, which also has to be adapted to suit the needs of science education. Ideally, both activities leave tangible traces in their respective spaces, and over time, both spaces become the expression of a true mixture of both “subjects,” and in some ways, they become increasingly similar.

2) “Everyone get together!”: messy co-location

Combine a range of activities in one large room, each student/group “doing their own thing in parallel”. In this scenario, it is essential to give participants the freedom and time to wander around and “visit” each other. A “social point” where participants can hang out and exchange ideas is essential to create opportunities for interaction. This social component is crucial for success! You will see how – even if the activities seem unrelated – the participants will start exchanging ideas and influencing each other.

3) “Everything in one place”: the creative circuit training

A group of participants is tasked with developing a joint project that requires collaboration and input from multiple disciplines. This could be a new product that necessitates design, imagination of future uses, research, technology, prototyping, and testing. All the tools and facilities that are necessary to develop this product should be located in one large space, with participants “rotating” through the facilities as needed. The focus is on the process, rather than a single discipline. This should create a true trans- disciplinary environment. Maybe the group even changes the idea for the product on the way and comes up with something much more innovative. And don’t forget the social space where the group can produce the most important outputs: good ideas, fun and mutual understanding.